The past eighteen months have been some of the most challenging in our recent history. In addition to its human cost, the Covid pandemic has put a huge strain on all economic sectors, not least the cultural one.

With the easing of lockdown restrictions in the UK, London is now emerging from the torpor brought on by the virus. Quite understandably, getting back to business as usual is the catchphrase of the hour, but will things actually revert to a pre-Covid normal?

If we were to consider the art world, the epidemic and social distancing policies have forced a rethinking of the role of digital technology and the way art can be experienced by reducing the dependency on physical presence. Although already underway, the process of digitisation within the arts sector has dramatically accelerated during the health crisis, helping to keep the industry going despite the hardships of the pandemic.

With its far-reaching consequences impacting the way art is produced, exhibited and consumed, it is unlikely the digitisation process will ever prove reversible. It is yet premature to say, however, whether the so-called digital revolution will set off a truly profound structural transformation within a rather conservative sector – a transformation that many advocate for, in hopes it will shape a more democratic, broad ranging and inclusive industry.

Among those who believe the digital shift offers a concrete opportunity for drastic change within the art world is artists collective Wells Projects.

Originally born as an artist-led, not-for-profit venue in Battersea, South West London, Wells Projects engages in work around ideas of diversity and communality. The collective cultivates a hands-on, cross-disciplinary ethos to promote a collaborative approach to the design and curation of art events between artists, facilitators and audiences.

At the outbreak of the pandemic, when lockdown became unavoidable, Wells Projects, as many other players, decided to go digital. They organised The Digital Commune, a series of online participatory projects aiming to create a virtual space for strangers to come together and experiment.

One of the projects from the series, Cryptocartography, was recently presented in a new iteration during Wells Projects’ residency with Lateral Geographies – the online artist in residence programme curated by 1883 Arts Editor. Drawing on the experience of our spaces (extending across work, leisure and entertainment) narrowing during quarantine, Cryptocartography foregrounds an idea of art as therapeutic process, one that helps us make sense of things in a pandemic world reeling from uncertainty and tragedy.

1883 Arts Editor sits down for a chat with the members of the collective to discuss their residency and upcoming projects, and to get their take on how the digital revolution is expected to reshape the art industry.

How did the collective come together? And how many artists/curators/creatives contribute towards Wells Projects?

There are three key members of Wells Projects: Charlie Hawksfield, Kariem Ismail and Viktoria Szanto, although we have a very loose structure with lots of curators, creatives and artists dropping in and out. We work on a project-by-project basis, and we aim to include as many voices as we can in each project. An important guiding principle is that we never turn proposals away. Wells Projects started with a space. We operated from a disused, abandoned nightclub called the Artesian Wells in Battersea for three years. At the start we had no plans to become an artist-led initiative, we didn’t even have a name for the first 4 or 5 shows, but word of mouth kept us busy and after a while we realised we had something people were interested in. We built an inclusive network over the years, meeting hundreds of artists and creatives. Around a year ago we decided to start the collective. We had come together really through lockdown and it felt like the right thing to try new things, especially as the original project space was becoming less certain and physical art venues were going through a difficult time.

How do you function as a collective? What is your working process?

We try to facilitate projects that benefit as many people as possible. When we had the space, we made a decision very early on to never charge the artists or the audience anything. If this financial decision was taken away, there would be a totally different atmosphere to everything. The way we work, we risk not being taken seriously by some, and we often operate on a shoestring budget, but the benefits are huge: people are relaxed, generous and free to try things in a way they would not be if they had to pay for the privilege. We also want to push the boundaries of our practice outside the traditional art circles and art spaces. We have run projects in cafes, clubs and even on the streets, involving dancers, opera singers, queer culture advocates and zine-makers. We have made connections with our local community and with other art spaces. We spend a lot of time trying to maintain this network because it leads to interesting coincidences and collaborations. Communities are generative. We want to argue that a community can produce incredible things, even though the term is so often just utilised as a passive buzz word, or something that burns money just to maintain itself. Communities literally mean groups with a thing in common and if you can provide that commonality and the right encouragement, then you can make amazing things, just like the Cryptocartography models.

What is the background of the people comprising the group?

Charlie: I am a practicing artist, but my educational background is in Humanities. I studied Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths and I loved it. The courses I studied are no longer going because the government is unwilling to spend money on non-vocational learning, which was the whole reason universities were created in the first place.

Viki: I am a creative with a practice focusing on collaborative processes and an interest in using art to facilitate learning and healing, without worrying about the outcome or stressing about the pressure of “being good.” I worked in museum education and special needs education for a while and now I work at a charity supporting unpaid carers.

Kariem: I am a visual artist with a background in Software Engineering. As a freelancer, I have worked with entities such as the BBC, as well as artist-led NPO’s. My interests lie in how technology and art are intertwined in a way that is constantly creating a need for their evolution, together and separately, and how to use this interdisciplinary concept to bridge multidisciplinary communities and create new breeds of art.

What would you say is the glue that holds you together?

Charlie: Good question! I think we all want to see the same thing – this thing isn’t an actual finished product, but it is some sort of set of conditions which allows sustainable, surprising and experimental projects to survive in an extremely hostile environment. When we started doing shows, I was so surprised at the hurdles artists had to jump to get just the bare minimum help. I was really shocked at some of the feelings of hopelessness young artists were telling me about once they had left art school and began trying to make it in London. This model of a high stakes, winner-takes-all game that began to emerge just made no sense to me, it’s such a waste of brilliant minds with practical skill. I think all of us felt that and we wanted to try and provide platforms and prompts where we could to ease the process of getting started, we wanted to create supportive communities as well as safe spaces to try things out, take risks, collaborate and get back to enjoying what you are good at rather than constantly struggling to stay afloat.

Viki: Having the same vision and motivation like Charlie said are important, but I think personal friendship and mutual respect are also essential. We all have different strengths and we try to play to them when we can.

At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic you decided to go digital and ran The Digital Commune. Can you tell us what the project entailed?

The project series was really our first step into the digital realm and our first experiments with facilitating online projects using the same ethos we had when we were running a physical space – these being collaboration, experimentation and openness. It was very trial and error in the beginning, and a challenge, as it was for so many in the art world, to continue producing interesting and interactive projects without the luxury of physical closeness. It wasn’t all bad though, as having to adapt and think around these new limitations, we got to work with participants from all around the world. The Digital Commune included four projects. The very first week of lockdown, we wrote a poem that was assembled from lines submitted to us online and also added to by passersby, as we wrote the poem on the sidewalk by our HQ. We also had a music project: a song entirely consisting of found soundbites that participants submitted – a kettle boiling, birds chirping, a cough etc.– sounds that we all became very aware of in quarantine. The third project, Clocked in, was a short film, once again made up of footage participants submitted to us, and accompanied by text, explaining a day in their lives, directed by Kariem. Lastly, we piloted an early version of Cryptocartography that was then a simple map-drawing exercise designed to help people orientate in their new and limited surroundings, and to draw from memory to cope with loss of space brought about by the lockdowns.

Your ongoing project, Cryptocartography – currently on view on Lateral Geographies – was originally part of The Digital Commune; how did Cryptocartography first develop?

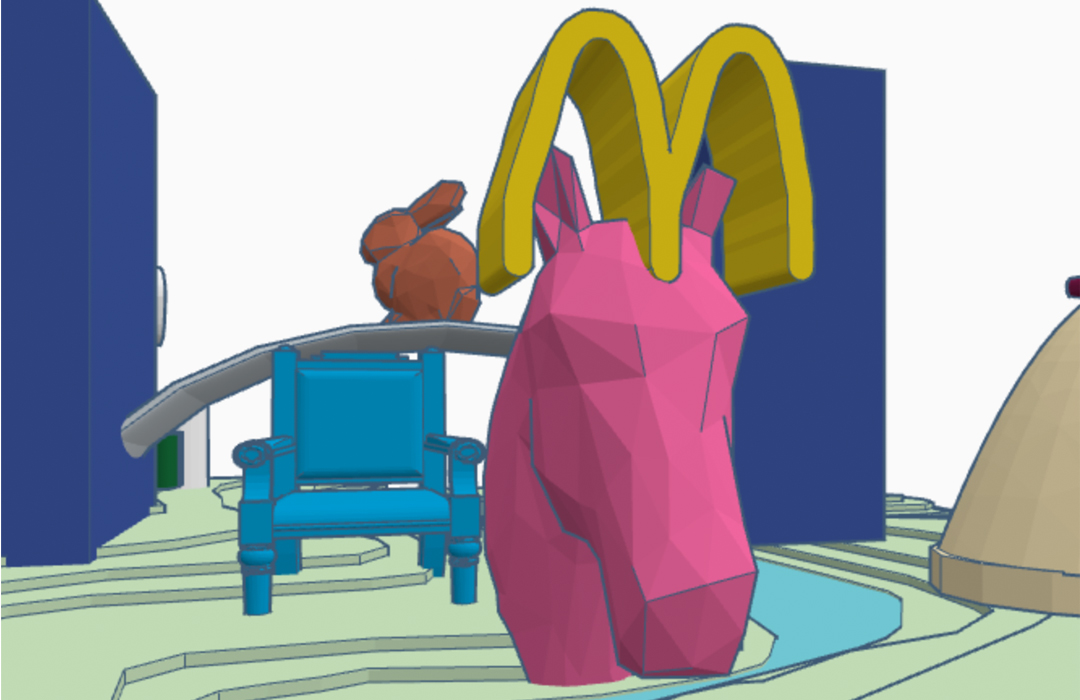

Cryptocartography outlasted a lot of other Digital Commune projects because it is a relatively simple process that produces surprising and totally unique results every time. We were really playing with the idea of the exquisite corpse format- like the poem written by everyone blindly writing a line, or everyone drawing a figure on a folding piece of paper. Cryptocartography tried to make a communal, shared space out of people’s imagined spaces and the idea developed as we tried to make a collaborative, equisite-corpse-space in the fairest way possible. It really feeds from the idea of artworks that have multiple authors, who set about working together in a non-hierarchical structure, with different backgrounds and experiences, to create something community-generated. We then were lucky enough to do a series of workshops as part of the Phoenix Art and Health Project in collaboration with Green Close and the NHS, which really helped us crystallise the mental-health focus of the process.

What are the similarities and differences, if any, between Cryptocartography as it is presented on Lateral Geographies and its previous incarnations?

Lateral Geographies gave us the chance to try out the project on Mozzilla Hubs. This was a tip we got from our friend Joe Moss, who was running a project attempting to create a multi-character avatar called Actual Orc. Hubs is really based on de-centralised environment making, which fitted our working process and way of thinking. Hubs is a buildable VR digital space which, like TinkerCAD (the software we used in previous iterations) can be accessed by many people, like a multi-player game. Basically, Zoom crossed with Minecraft! After designing the 3D map together, we met up with all the participants of the project and caught up online next to the model. It is another step towards making this project a totally collaborative process and a shared digital experience from start to finish.

The health crisis has accelerated the digitization of the cultural industry; what is your take on the future of the arts sector? And as a collective, how do you see your practice evolving and developing in the near future?

Charlie: The digital realm is becoming less and less separate from the non-digital realm, the boundaries will merge more and more no matter how much better or worse the pandemic gets. I recently went to an RCA show and I can’t remember seeing a single piece that didn’t have a screen in it. I am more interested in thinking about how the digital realm is going to be creatively colonised: will it be by individuals with high ideas of how societies should be (same as any fervent coloniser) or will it be by facilitators, communities and collectives? I am interested in infiltrating the assumptions of these systems (which mirror all the biases and faults of non-digital systems) and creating an alternative space. In the Artesian Well Nightclub, our original art space, people felt there was that different atmosphere, one that encourages and supports instead of streamlining, individualising and commodifying. I hope there will be similar spaces in the growing digital world.

Viki: This might be a cliché, but the future of art is now digital, both in terms of art-making and consumption. We are living in a world full of uncertainties and for numerous organisations it is also a safer bet to remain online – a lot of energy and funds can go into planning in-person events that have to be cancelled last minute. It is really up to us to make the digital space as accepting, inclusive and approachable as we can. We have to be very mindful not to recreate the old systems that governed the art world, because we rarely get such a fresh start to do things differently. Unfortunately, NFTs, the current golden child of the digital art world, have not proven to be the “democratising” force as they first seemed to be, and a big reason for that is the focus on capitalising on art: selling, buying, and the power dynamics that come with it. At least for us at Wells, a way to combat this is to get rid of the idea of ownership in creative processes altogether (and to eliminate money-talk as much as we can!).

Besides the residency, what have you been working on lately?

We have a few projects on the go: we are making a limited run of T-shirts designed by artists who we have worked with in the past, this will raise money for the Maudsley Crisis Ward where one of the participating artists works. We have also developed a project called Wells Walks that provides weekly walks and toolkits curated by artists and support workers. These walks are designed to build an archive of participant-sourced material and provide non-medical, nature-based therapy for mental wellbeing. We are also cooking up an artist-led video series/moving image/cooking show extravaganza, think Fanny Craddock mixed with the Cremaster Cycle! All the while we are tentatively looking for a new space and have a pop-up exhibition series as part of the Westminster council’s Voids Activation programme. This will be a wild DIY programme of painters, dancers, set designers, drag acts and performances, called The Lost Nightclub as an homage to our first home, where Wells Projects was born. It will take place in August, so stay tuned!

And what have you got lined up for the future?

All our energies now are really going towards the Westminster project. The Lost Nightclub is a bit of a farewell to the Artesian Well where we spent our formative years, we will display a few salvaged bits and bobs from the building and try to encapsulate what the place was while it was allowed to exist (it has now been gutted and converted into flats). We will be extending the ethos of the space into the centre of London with a chaotic, camp, clumsy approach to making spectacles, including lots and lots of artists who are gonna make the month a totally unique and unpredictable experience! Keep an eye on @wellsprojects for updates.

Words and interview by Jacopo Nuvolari

©1883 Magazine